During the next thirty years, the term gens de couleur libres, or free people of color, was typically used to denote people who arrived in New Orleans from the Caribbean already free or who were born into freedom as the second generation of free blacks. (8) From the outset free people of color were detached from their ancestors' experiences of slavery and African identity.

The community thrived in New Orleans. Free blacks were assimilated into the dominant French culture; many were slave owners themselves; many were well-educated business owners and professionals; and many were craftsmen. (9) As early as 1724, Bienville published the Code Noir, or Black Code, which regulated the behavior of both slaves and slave owners, (10) and influenced the behavior and treatment of free blacks, with manumitted slaves enjoying the same rights given to those born free:

By the 1740s, New Orleans was a complex, multifaceted society. Nonwhites outnumbered whites, and the middle stratum of free blacks was poised to become the artisans and tradesmen on whom New Orleans would come to depend. (12) In 1763, after the Seven Years' War, colonial Louisiana was transferred to Spain by the Treaty of Paris. Initially free people of color and slaves feared Spanish rule, but this fear proved unfounded. Under the Spanish, free blacks were given even more security and rights than they had previously enjoyed.

Spain, like France, was unsuccessful in making Louisiana profitable, but it did actively revive the slave trade. After twenty years of Spanish control, Louisiana's population in 1788 had grown from just over eight thousand to more than forty thousand, of which 19,737 were free persons (white and black) and 20,673 were slaves.

(13) After the region briefly returned to French control in 1802, Napoleon sold the Louisiana Territory to the young United States in 1803. By this point, it was estimated that as much as 30 percent of the city of New Orleans was gens de couleur libres, and others continued to immigrate there. In 1809 nearly three thousand highly skilled free black refugees from the slave revolts in Haiti arrived in New Orleans by way of Cuba, and over the next thirty years the free black population grew steadily. (14)

Quote of the day

A person without a History is like a person lost in the wilderness

|

New Orleans became one of the United States' busiest ports by the third decade of the nineteenth century, and the overall population continued to grow, fueling the demand for fine furniture and the trappings of culture. Cabinetmakers, import companies, purveyors of high-end goods--the business of culture--blanketed the city, which, even then, let the good times roll.

At the heart of much of the furniture-making activity were free black cabinetmakers, a vibrant if fleeting community whose history has been all but lost to this day. Still, what can be gleaned is exciting: not only did this tightly knit group comprise one in four of the cabinetmakers working in the city in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, but they were artisans with strong styles, broad influences, and deft skills.

The most compelling period for freemen of color as cabinetmakers was clearly from 1810 into the 1840s. Legal and public documents reveal that during this time free black cabinetmakers and carpenter-joiners played a defining role in establishing New Orleans as a center for the production of fine furniture in the South. (15) Consider the numbers: one review suggests that there were more free black craftsmen and business owners in New Orleans between 1810 and 1840 than in any other city in the United States. (16) In 1822 the New Orleans city directory listed fifty-three cabinetmakers, thirteen of whom were freemen of color. A year later, the directory listed fourteen free black cabinetmakers.

A thriving system of apprenticeships grew within the community. Between 1809 and 1830, free black cabinetmakers held eighty-two apprenticeship contracts, while white cabinetmakers reported only fifty-two. (17) Jean Rousseau (w. 1810-1837) had the largest number of apprentice contracts with young freemen of color--twenty-five between 1813 and 1833. (18) His earliest apprenticeship contract is recorded with Dutreuil Barjon Sr., who would go on to become one of the city's most renowned furniture makers. Presumably many of the other young men Rousseau trained also continued on in the cabinetmaking trade, although none has been identified with extant pieces of furniture today.

|

An American Walnut Armoire, c. 1835-1850,

New Orleans, in the manner of Dutreuil Barjon, the rectangular ogee molded cornice above a frieze centrally decorated with scrolling leaves, the paneled doors enclosing a void interior and over a pair of drawers, on bracket feet, height 91 in., width 63 in., depth 22 in. [$3000/5000]

Provenance: A Vieux Carre’ Museum collection.

|

|

|

| |

By 1820 small family dynasties of free black craftsmen--the Barjons, Glapions, and Dollioles--were becoming prominent within the artisan community, and very likely throughout the city itself. Remarkably, even toward the end of their period of influence, between 1830 and 1845, free black craftsmen showed resilience. When the city witnessed the growth of furniture dealers who sold manufactured products imported from elsewhere, there was an overall decline in the number of cabinetmakers. Yet the number of free black cabinetmakers actually increased. (19)

[FIGURE 7 OMITTED]

It was long thought that virtually no furniture made in Louisiana between 1750 and 1830 had survived the ravages of climate, fire, and changing tastes. (20) However, research undertaken in the last thirty years has proven this to be untrue, and continuing study has led to the discovery of an increasing number of pieces made by freemen of color. While their work remains relatively rare, what has been identified affirms the quality of their craftsmanship.

However, given that Robin was writing when the free black cabinetmaking community in New Orleans was in its infancy, this assessment, particularly the comparison with Parisian craftsmanship, is most unfair and almost certainly reflects a racial and national bias.

|

|

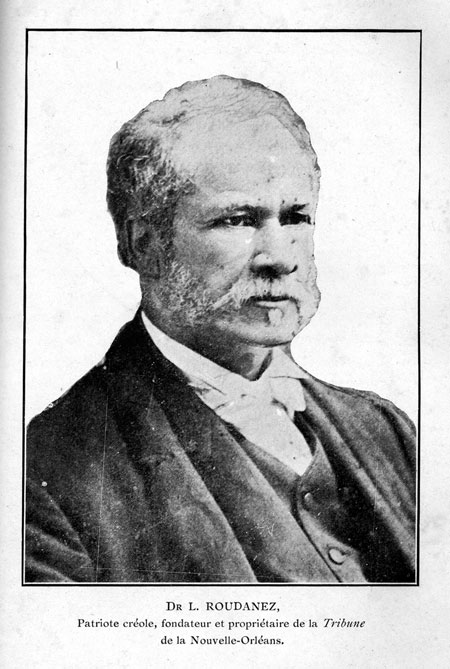

19th Century Creole |

|

|

|

In 1810, a mere seven years after Robin commented so negatively on cabinetmaking in New Orleans, Celestin Glapion made the notable armoire in Figure 4, the earliest known piece that can be linked to one of the city's free black cabinetmakers. (22) Constructed of American black walnut and cypress--a local, rot-resistant timber--the armoire is similar to the typical Louisiana example in Figure 3.

Both pieces have the strongly angular contours associated with the French Directoire style, which technically dates from about 1799 to 1805, although the rococo style is apparent in each of them in the cabriole legs, scalloped skirt, delicate escutcheons, and carved hoof feet.

As this comparison indicates, despite their active role in the New Orleans furniture trade, free black cabinetmakers did not develop an identifiable style of their own. Like most furniture from the city between about 1810 and 1850, theirs displays a limited use of decoration, allowing the grain of the wood to speak for itself, and generally reflects market demand and emerging American tastes.

The region's most distinctive style is the so-called Creole style, which developed in the early nineteenth century as a blend of the attenuated lines of Louisiana French provincial furniture, West Indian influence, and Anglo-American inlay and brass ornamentation (see Fig. 3).

By 1830 the popularity of this provincial Creole style came to an end, and furniture made in New Orleans fell into step with the popular styles that arrived from the East Coast. Largescale mahogany furniture with bold sculptural carving and supports typical of the classical revival, particularly of its later manifestation, the Empire style, (23) was made in the city. The dining table in Figure 10, which remains in the Hermann-Grima House in the French Quarter, is a fine example that may have been made by a freeman of color. (24)

No Other Culture or People can boast a greater cultural Diversity |

|

|

Indeed, two hallmarks of the late Empire style were already evident in New Orleans furniture, namely monumental proportions intended to suit the large rooms and high ceilings in plantation houses, (25) and the use of large expanses of highly figured mahogany veneer as a decorative element (see Fig. 8). By contrast, the use of gilded and carved ornament often seen on Empire style furniture was very limited in New Orleans. The daybed by Dutreuil Barjon Sr. in Figure 5 is typical, with its large, graceful yet simple curves and dark veneer.

Born about 1799 in Jeremie, Saint Domingue (later Haiti), Barjon arrived in New Orleans with his mother in 1813 and was apprenticed to Jean Rousseau. By 1823 he had his own shop, located at 245 Royal Street, (26) between Dumaine and Saint Philip Streets, one of the French Quarter's premier addresses even today. Eleven years later, his operation was still going strong, for he advertised in Michel's City Directory in 1834 that he had "enlarged his establishment," expanding to 279 Royal Street, where he offered "to the public a large assortment of Furniture made in this city, and in the newest and most fashionable style" (see Fig. 6).

There is evidence that Barjon imported furniture to sell alongside his own products to supplement his income. In 1835 he and Christopher W. A. Voigt (w. c. 1835-1840), a white German cabinetmaker in New Orleans, agreed to a year-long partnership in which they would import furniture from Hamburg and Berlin. As the agreement notes, Barjon chose the pieces that he believed would sell in the New Orleans market:

It has been thought that Barjon's German imports and contacts actually helped introduce the German Biedermeier style to New Orleans. (28) But he should not be given this distinction alone. New Orleans had a large German population by the mid-1800s, and some of these immigrants probably brought Biedermeier furniture with them, or they were certainly familiar with the style. The taste for classical designs in the 1830s, coupled with a first-generation German population, suggests that imported pieces in the Biedermeier style simply sold well, with Barjon, a keen businessman, tapping a ready market.

Nonetheless, in 1843 he filed for relief from his creditors. An inventory of his assets and liabilities taken at that time lists tools used in cabinetmaking and some of his merchandise, which included a large mahogany armoire valued at eighty dollars, a mahogany desk at sixty-five dollars, a cherry bedstead at forty dollars, and a regular mahogany bedstead at sixty dollars. (29) In 1854, still plagued by credit problems, he left New Orleans for Paris. (30)

To date the daybed shown in Figure 5 is the only known object by Barjon. (31) Happily, more pieces by his son, also a very capable cabinetmaker, have come to light. Dutreuil Barjon Jr. was born in New Orleans in 1823 and is first listed as a carpenter-joiner in the city directory in the late 1840s, working for and managing his fathers French Quarter shop. By 1855 he had acquired the shop, which was still listed in the New Orleans city directory that year, but then neither Barjon Jr. nor his newly acquired store appears in the directory for the next five years. He and the shop are listed again between 1860 and 1867.

|

An American Walnut Armoire, c. 1835-1850,

New Orleans, in the manner of Dutreuil Barjon, the rectangular ogee molded cornice above a frieze centrally decorated with scrolling leaves, the paneled doors enclosing a void interior and over a pair of drawers, on bracket feet, height 91 in., width 63 in., depth 22 in. [$3000/5000]

Provenance: A Vieux Carre’ Museum collection.

|

|

|

| |

Barjon Jr. made the mahogany semainier shown in Figure 1 about 1850. Decidedly Biedermeier in style, even though made almost half a century after the style's heyday, it is very similar to German chests of drawers made between about 1810 and 1820. (32) Barjon Jr.'s has bun feet and a molded cornice while German examples do not have a rounded edge in sihe semainier is, however, also progressive because chests of drawers were not popular in the New Orleans region until the late nineteenth century, the ubiquitous armoire being the favored storage piece.

Why Barjon Jr. chose to make this form can only be speculated. But due to the German population in New Orleans, and considering that the third wave of German immigrants to New Orleans were professionals and intellectuals, he likely saw a market opportunity and exploited it.ght. The grain of the mahogany veneer creates the decorative interest, an important signature of New Orleans design as well as one of the tenets of Biedermeier design. (33)

The mahogany armoire of about 1840 in Figure 9 is also labeled by Barjon Jr. It displays the bold proportions and highly figured veneers characteristic of New Orleans furniture, but it is so large that it makes other large armoires seem small in comparison (see Fig. 8). The shaped and molded cornice relates it to furniture promoted by John Hall (c. 1809-1855) and the Meeks firm in New York City (see Fig. 7). Overall, it falls within the Empire style, evidence of Barjon Jr.'s range as a craftsman. (34)

Finally, the lady's mahogany dressing table with looking-glass frame in Figure 2 and the headboard in Figure 11 exemplify his ability to keep pace with the ever-changing tastes of the period and to work in a variety of styles. Dating from about 1845 to 1850, they belong to a four-piece bedroom set. The cabriole legs, scrolled feet, stylized leaf and floret carving on the table, and the central shell motif with stylized leaves and rosettes on the headboard bespeak his familiarity with the rococo revival style.

(35) The looking-glass frame appears as if it is in constant motion with its dramatic, undulating scrollwork. Barjon Jr.'s table and looking-glass frame are possibly after a similar example from the design manual by Desire Guilmard, Le carnet de l'ebeniste Parisien: collection de meubles simples (c. 1845). (36)

By the late 1840s, the free black cabinetmaking community was in decline. From 1842 to 1855, only five or six free black cabinetmakers were listed each year in the city directory. The reasons were many: the looming Civil War; new racist legislation aimed at the black community, and the resulting exodus of the free black population from the city; and, of course, increasing mechanization and the mass production of furniture. Collectively, the impact was devastating and the livelihood of all cabinetmakers--black and white--was irrevocably changed. (37)

For the free black craftsmen, the three-tiered caste system they once belonged to collapsed into two--white and black. A society that previously supported a furniture trade in which free black cabinetmakers thrived was systematically dismantled, the accomplishments of these cabinetmakers buried, and many invaluable pieces likely lost. However, the dearth of pieces attributed to the freemen of color should not be considered an indication of their insignificance. As attention and awareness turn to this group, it is hoped that more examples of their craftsmanship will come to light.

This research was undertaken at the Sotheby's Institute of Art, London, and in the great city of New Orleans. A very special thank you to Wendell Garrett, Peter Patout, and Cybele Gontar. Also, thank you to Jack Holden, Jessica Dorman, Anne McCall, and the Historic New Orleans Collection. Finally, many thanks to Derrick Beard

Read the Original Publication click on source