According to

the legend, the Cane River colony owes its beginnings to a

woman known as Marie Thereze, or Coincoin. Of African origins.

She was from her childhood a slave in household of the commandant

of theNatchitoches post, Sieur Louis Juchereau de St. Denis.

The legendary Coincoin was outstanding even as a slave; her

natural intelligence, her loyalty, and her devotion to duty

soon made her a favored servant in the St. Denis household.

Ultimately, these qualifications were to earn for her the

one thing she most desired: freedom.

|

Supposedly the

event which gave her the chance to break the bonds of slavery

and take the first step toward becoming the founder of this

unique society was the illness of her mistress.

Mme. de St.

Denis was in bad health, and the local physician could find

no cure. Others were brought in from New Orleans, Mexico,

and even France; their efforts were to no avail. The family

was counseled to accept the will of God. But one member of

the household refused to despair.

Marie Thereze, who had gained

from her African parents a knowledge of herbal medicines,

begged for an opportunity to save the dying mistress who she

loved deeply. In desperation the family yielded to her entreaties,

and to the bafflement of the educated physicians she accomplished

her purpose. In appreciation the St. Denis family rewarded

her with the ultimate gift aslave can receive.

The gratitude

of the St. Denis family, according to the legend, did not

end with Marie Thereze’s manumission. Through their

influence, she applied for and received a grant of land which

contained some of the most fertile soil in the colony.

With

two slaves given to her by the family and many more whom she

was to purchase later, this African woman carved from the

wilderness a magnificent plantation.

The center

of this emerging agricultural empire was Yucca Plantation,

still extant and more commonly known as Melrose. It was here,

allegedly, that Marie Thereze erected her home and auxiliary

plantation buildings, and here again she seems to have exhibited

her individuality, constructing her buildings, supposedly,

in African style, adapted to Louisiana conditions and native

materials.

Not just any Frenchman did she choose to share

her life, but a man reputed to be the scion of a noble family,

Claude Thomas Pierre Metoyer. As her children entered adolescence

and made their First Communion, according to religious customs

of that time, Marie Thereze carved for each of them a wooden

rosary. At least one such rosary was treasured by her descendants

until well into the twentieth century.

Before her

death Marie Thereze divided her extensive holdings among the

children she had borne to Metoyer.

For almost a half century

following her death, the Metoyers of Cane River enjoyed a

wealth and prestige that few whites of their era could match.

Gracious and impressive manor homes were erected on every

plantation, furnished not only with the finest pieces that

local artisans could make but also with imported European

articles of quality and taste.

Private tutors provided the

children with studies in classics, philosophy, law, and music.

The young men of many families were sent abroad for the “finishing

touches” which only a continentaluniversity could provide.

“The

Forgotten People”

Cane River’s Creoles of Color

By: Gary B. Mills

Louisiana State University Press

Baton Rouge and London |

In spite of

the racial limbo into which their origins placed them, the

men of the family were accepted and accorded equality in many

ways by the white planters. It was not uncommon to find prominent

white men at dinner in Metoyer homes, and the hospitality

was returned.

White planters brought their families to worship

in the church erected by the colony, the only one in its area

for many decades. In a time and place which there were no

banking institutions, the Metoyers freely lent and borrowed,

advised, and stood in solido with their white friends and

neighbors.

They were known as “French citizens” long after Louisiana was sold to the United States, and they

held themselves aloof from the waves of “red-necked

Americans” who settled in the poor pine woods that surrounded

the rich Cane River plantations.

The Colony

was founded by Metoyers, but each successive generation saw

the introduction of two or three new family names. Gens de

couleur libre from Haiti and New Orleans settled on the Isle, and those whose background passed inspection intermarried

with the community.

Wealthy white planters of the parish arranged

marriages for their own “children of color” with

the offspring of their Metoyer friends. This new blood, carefully

chosen, did much to protect the colony from the genetic hazards

of too frequent intermarriage.

For more than

a half century this self-contained colony flourished on Cane

River. The people founded not only their own schools and church

but also their own businesses and places of entertainment.

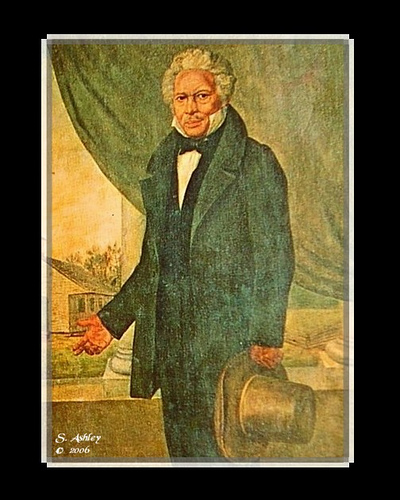

The family’s patriarch, Grandpere Augustin, who was

the eldest Metoyer son of Marie Thereze, served for decades

as judge and jury; his word was law and went unquestioned.

It was his dream to make of the Isle a place for his people,

not merely a home but a refuge against the new breed of greedy

Americans. By the end of their era of affluence, the family

had almost totally achieved the goal laid out for them by

Grandpere Augustin.

Cane River’s

gens de couleur libre, like other southern planters, supported

the doomed cause of the Confederacy; and they, like most planters,

suffered the depredations of war and the financial ruin of

Reconstruction.

Unlike their white neighbors, however, they

found that after Reconstruction their ruin was complete, since

the reactionary political climate of the Redeemer period throttled

their economic opportunities. The “liberation of all

men” shackled the people of Isle Brevelle with anonymity;

the equality proclaimed by the Union lost for them their special

prestige

. The colony turned inward even more, finding now

that they must not only protect themselves against status-conscious

whites but also against ambitious black freedmen.

| Cane River Colony 1930's Archives |

|

|