|

|

|

|

The Quadroons |

|

| |

|

|

|

Link 1 |

Link 2 |

Link 3 |

| |

|

|

Link 4 |

Link 5 |

Link 6 |

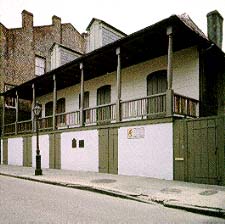

One of the oldest buildings

in New Orleans bears the strange name Madame

John's Legacy for a fictitious woman of color. Ironically,

that is the only name to survive from a unique group of free

women of color who became mistresses of French men.

Madame John, according

to a story written by George Washington Cable in the 1860s,

was a quadroon, a light-skinned mistress of a French-Creole

man, Monsieur Jean. Upon his death she inherited his estate,

as he had never married a woman of his race. In the story

Madame John (jean) is persuaded to sell the property, but

the bank where she invests the money goes under and she is

left destitute to raise her daughter.

| |

|

|

| |

Excerpts by..... Eleanor Early

The most beautiful woman I ever saw was the colored wife of a Negro diplomat from Haiti, a pale girl with skin like gardenias. I met her at a reception at the President's Palace in Port-au-Prince. Her eyes were the color of Haitian bluebells, which is the shade of delphinium which is a cross between clear blue and purple.

Her mouth was a pomegranate cut in halves, and the wings of her blue-black hair were the wings of a Congo thrush. her maiden names was Dumas, and she was descended from the great Dumas, père and fils. The first Dumas was the son of a French marquis and a colored woman from Santo Domingo. Some of Dumas'sdescendants are white and some are black.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

A Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenbach

. . . was most favorably impressed by the Quadroons. He visited New Orleans in 1825 and attended a Quadroon Ball where he danced with the girls, and met their mothers.

The duke, who was a brother-in-law of William IV (the uncle of Queen Victoria) said the Quadroons were "the most beautiful women in the world." if Victoria heard that, she probably washed her hands of the duke. . . .

|

|

For several generations,

1790 to 1865, it was not unusual for a young white Creole

man to take a free woman of color as his mistress, set her

up in her own house and have several children with her before

he reached his mid to late twenties and married a French woman

to raise his legitimate family.

This was different from

plantation life throughout the South where it was well known

that some white masters consorted with their female slaves.

Those relationships were not openly recognized, and children

born of such liaisons were considered black and slaves, taking

their status from their mothers.

In New Orleans placage, the

local term for open miscegenation, did not involve slave women

but rather free black women who had a limited degree of choice

as to whether they were to become a mistress and whose mistress

they would be.

The relationship was

often a long-lasting one, sometimes continuing long after

the man married. Children born in placage generally took their

white father's last name, were supported by him, and even

in some cases indirectly inherited large sums upon his death.

Daughters were often raised to become mistresses of the next

generation of white Creole men, while sons were sometimes

sent to Paris to be educated, as there were few schools for

such children in New Orleans.

|

Unfortunately no exact

history of this placage system exists. It is not know how

many such liaisons took place, how many men supported their

families of color, nor how many men like Monsieur Jean never

married. Quadroons were known to be loyal to their white lovers.

If a man deserted his family of color, the quadroon often

had to work to support herself and her children . Professions

such as hairdresser, seamstress, and shopkeeper were often

practiced by such women; other times they opened their homes

as guesthouses. Later on American men and planters from upriver

also kept quadroon mistresses in New Orleans.

The origin

of the placage system is uncertain. The custom may have been

imported early on by French and Spanish settlers from Santo

Domingo and the West Indies where it was practised widely.

Another factor would have been the scarcity of marriageable

white women for the Creole men, and conversely of available

free men of color for free black women to marry. This imbalance

lasted up to the Civil War. The majority of free blacks were

apparently women; a census of the city in the late 1700s married

women of color numbered fifteen hundred.

|

|

|

|

|