CYPRESS, Tex. — Water is the enemy of plaster. Earl A. Barthé, the 83-year-old master plasterer of New Orleans, knows this deep in his heart. And so he waits.

For more than 150 years the Barthé family - like generations of other highly skilled plasterers, lathers, blacksmiths, masons, carpenters and contractors - has tended to its city's architectural soul. In an age of drywall, New Orleans is largely handmade, a city where louvered cypress shutters and filigree iron galleries greet the morning.

From opulent Garden District drawing rooms to tiny shotgun houses in the Seventh Ward artisans like Mr. Barthé - and their fathers, grandfathers and great-grandfathers before them - quite literally made their mark, their signatures, placed pridefully but hidden on wooden laths beneath the plaster.

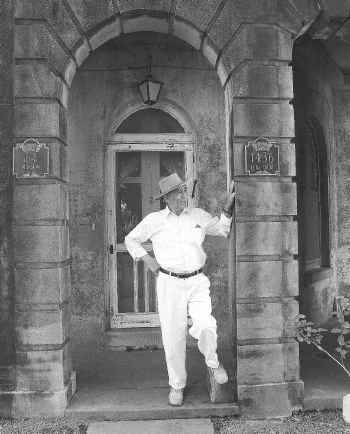

On Thursday Mr. Barthé, who has been called the Jelly Roll Morton of plaster, will put on a borrowed suit and a broad-brim hat sent by a family member familiar with his J. R. Ewing style to accept a now-bittersweet award from the National Endowment for the Arts: a National Heritage Fellowship, which carries a no-strings grant of $20,000.

One of the few building artisans ever to be so honored, Mr. Barthé, who has been encamped since Hurricane Katrina with seven family members in a rented ranch house in Cypress, about 25 miles outside Houston, will join past winners like B. B. King and Doc Watson.

In his pocket he will carry the plaster-specked leaf tool for mitering elaborate stepped corners of cornices that he inherited from his father, Clement J. Barthé. The tool, discovered on the floor of his pickup truck after he and his family drove to Cypress, is his lone working remnant of the trade: he caught a glimpse of his workshop near the old St. Bernard Market, its historic arches barely visible above the fetid water, on CNN.

While the world has long celebrated the musicians and chefs of New Orleans, the cultural roots of the city lie, too, in the unsung generational know-how and anonymous public work of skilled artisans like "Mr. B," as he is known. His forebears, of mixed Creole and black descent, migrated to New Orleans by way of France and Haiti. Many of the early artisans settled in the Seventh Ward, among them Mr. Barthé's great-great-grandfather Leon, who founded the business in 1850.

"Daddy said Leon could look at you and produce you out of plaster," Mr. Barthé recalled, swatting no-see-ums in the garage, where he has felt most at home since the storm. "He was a super-master."

With 20 historic districts encompassing some 37,000 buildings, New Orleans has the greatest concentration of historic architecture in the country. In the minds and hands of the city's Creole plasterers, French and Sicilian carpenters, Italian and Spanish ironworkers and English and German masons lies knowledge of "St. Joe" bricks, made from pressed river mud, and wood and planks recycled from flatboats that made one-way trips down the Mississippi. They understand the warp and weft of what Theodore Pierre, an architect and mason who works in stone and brick, calls "le tout ensemble."

|

"They are the cultural memory," John Michael Vlach, a professor of American studies and anthropology at George Washington University in Washington who writes extensively on vernacular architecture, said of the city's multigenerational artisans. "They're the keepers of the treasure."

Unlike the situation in newer cities, rot, humidity and Formosan termites have long had their way with old buildings in New Orleans. So the city has always needed tenders of its heritage. Jelly Roll Morton's father, Ed LaMothe, was a bricklayer.

Allison Montana - the "chief of chiefs" of the Mardi Gras Indians, who was known as Tootie and whose coffin was flanked by his beaded sequined suits at his funeral this year - was a lather, installing the wooden battens on which plaster hangs. He was legendary among his fellow tradesmen for being able to drive a nail blindfolded and, it is said, for spitting nails in succession into his hands.

The importance of such artisans in New Orleans cannot be overstated, said Hilary S. Irvin, an architectural historian with the Vieux Carré Commission, a preservation agency that oversees the French Quarter. "This is one of the few places in the country where craftsmanship has been handed down over generations, much like medieval guilds or European church builders," he said.

Mr. Barthé has personally restored hundreds of the city's landmarks, among them the Saenger Theater, a 1927 movie palace that is a Florentine garden in plaster (now boarded up after the storm, but with minor visible damage), and the Sophie Wright house, an 1850's Italianate mansion in the Garden District (also boarded up but largely unscathed).

For 150 years Mr. Barthé, his father and his grandfather have repaired leaking roofs and other architectural ailments at St. Louis Cathedral on Jackson Square. The church, the backdrop for President Bush's televised address on Sept. 15, is in its third incarnation, the original having been swept away by a hurricane on Sept. 12, 1722, and the second lost in a fire in 1788.

When he is at work in his plasterer's whites, Mr. Barthé is lithe on the scaffold, launching into arias from "Carmen," his favorite opera, while pushing a template across a wet plaster wall to form a beaded frieze or another ornament. He turns to Muddy Waters or Ray Charles during tough maneuvers like the installation of a hallway ceiling medallion 18 feet up.

"Curves," he explained, "are conducive to the blues."

His own home in Gentilly Terrace, "an all-solid-plaster house, well constructed," he said - code for no drywall - appears undamaged from the outside, but its interior condition is uncertain. Like generations of artisans, he raised his children - six of them, from two marriages - in the Seventh Ward, whose blocks were once filled with names of local veneration like Barthé, Balthazar, Torregano, Dejeane.

|

||

More on the Master Plasterer......Click here |

The very term "Seventh Ward" was synonymous with top-flight craftsmanship. Many of its residents lived in modest shotgun houses with "Cadillac finishes," as Mr. Barthé put it: the living room ceilings were subsumed by huge buttery swirls of plaster, the backyards presided over by pink cement dogs and the stucco exterior walls inlaid with oyster shells.

The neighborhood's profusion of skilled black and Creole artisans, who built the French Quarter nearby, was a legacy of slavery, he said, sipping matzo ball soup freshly made by his 47-year-old daughter Terry, a testament to the diversity of both the city and the family palate.

"All the elite French- and Spanish-speaking rich white gentlemen had their ladies," he said, "and naturally, they had children." Growing up in the Seventh Ward, he said, the youngsters learned trades from an early age.

On weekends in the 1960's, when many people began migrating from cities to the suburbs, Seventh Ward craftsmen were still committed to the New Orleans version of barn-raising, embellishing each other's houses with abandon. The women would cook a feast of red beans, rice, fried fish and wild game. "The trick was to have lunch late," Mr. Barthé recalled. "After that the work got crooked."

In the days before trade schools, the ritual had a dual role. In addition to helping neighbors, "it was a chance for your father to see what progress you made," Mr. Barthé said. An incident from his childhood still burns hot: his own father saying, "You're not going to make it - that Tio boy is better than you." But not long after, he walked into a room and overheard his father telling someone, "That Earl is going to be a good plasterer."

"It was about bloodlines, the family name," he explained. "It was heartbreaking, but that was his way to teach me."

From 1954 to 1960, Mr. Barthé served as the union representative for Plasterers Local 93, founded in 1901 in part by "Old Man Peter," his grand-uncle Peter Barthé, and integrated, he said, "because they wouldn't let segregation interfere with the craft."

He remains steadfast in his faith in a material that has survived in New Orleans over 200 years but that, he readily acknowledges, can virtually melt off the lath when exposed to water.

Earl Barthé

|

|---|

"I don't think all of this has hit Daddy yet," said his daughter Trudy Barthé Charles, 49, who worked with him in the family business along with her sister Terry. "It hasn't hit me either."

The National Trust for Historic Preservation has asked Congress to approve $60 million to assist private property owners in New Orleans and the Gulf region in repairing historic houses. (FEMA funds are rarely available to repair private buildings.) The trust is also proposing a 30 percent tax credit to help with the repair of homes listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

With reports of ravaged structures collapsing in the Treme neighborhood and other historic districts, artisans and apprentices may hold a key to disaster recovery that embraces the city's historic character and avoids the generic development that Mr. Pierre, the architect and mason, who is also temporarily living in the Houston area, calls "architectural white noise."

"These men are living traditions," said Reed Kroloff, dean of the architecture school at Tulane University in New Orleans. "Now they are going to be a precious resource. They are the last living connection between New Orleans as it was and New Orleans as it may be."

|

In 2002 Mr. Pierre and Jeff Treffinger, an architect and carpenter, established the New Orleans Crafts Guild, a nonprofit training program, to try to address the growing shortage of young people interested in artisanry. That shortage is partly a result of the underfinancing of high school technical programs, Mr. Treffinger said, and "manual labor not being encouraged as a destiny." The program has already trained students from Booker T. Washington High School in the Ninth Ward.

Mr. Pierre, who is 54, said storm recovery should include "a cadre of young people," apprenticed to master craftsmen like Mr. Barthé, who might minister to a city in need.

"These buildings speak to us as people," said Nick Spitzer, a professor of folklore at the University of New Orleans and the host of the public radio show "American Routes," who is to present the award to Mr. Barthé in Washington. "They need curators."