Before you go another step, you need to know the proper pronunciation: Cajun (cay-jun) and Creole (cree-ole).

Who are these Cajuns and Creoles whose motif with the small c is on almost every other restaurant and gift shop in New Orleans? New Orleans' Chef John Folse, who opened a culinary school in 1988 in what was then the Soviet Union, was quoted by historian Mel Leavitt as saying the major difference between the two was that the Creoles ate in the dining room and the Cajuns ate in the kitchen.

In reality, the difference between Creoles and Cajuns is not quite so simple. In the strict definition, a Creole would have been white or black, either a full-blooded descendant of an early Spanish or French settler or of an African slave. The word Creole comes from the Spanish word criollo, which means literally child born in colonies, as opposed to a baby born in Europe or Africa.

New Orleanians "of color" were mulattoes, quadroons, and octoroons - children of relationships between full-bloods. To compound the ethnic stew, as late as 1873, public directories in New Orleans were calling anyone born in the city a "Creole." This meant there were German Creoles, Chinese Creoles, Jewish Creoles, and Bohemian Creoles, as well as those of French, Spanish, and African descent.

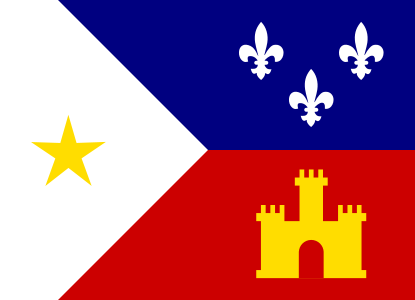

Cajuns, on the other hand, were descendants of French Canadians who had lived in Nova Scota since 1604. The land was so fertile there that the settlers called it l'Acadie, or heaven on earth. In 1713, the English seized control of the area after a war with France. The fiercely independent Acadians promised to remain neutral if the British crown would have demanded that the Acadians swear allegiance to the crown.

They refused, feeling that the authorities went back on their word, which, of course, they had. Face with rebellion, troops were sent in to confiscate the Acadian property and the entire population was ordered into exile. Some returned to Europe, some moved west into French-speaking Canada, and others went to other French colonies.

In 1765, Acadian political leader Joseph Broussard arrived in New Orleans with 200 of his family and friends. Life in the big city did not agree with them, so they moved to Breaux Bridge, Louisiana, and began farming. Over the next decade, these original settlers were followed by almost 10,000 settlers, among whom were several thousand refugees who had first gone to France and then returned to America in 1785. The Acadians' forced migration was immortalized in poet Henry W. Longfellow's Evangeline, first published in 1847. The epic poem told of two Acadian lovers separated by the exile. The term Cajun is a bastardized version of Acadian. Both whites and blacks in Lousiana can legitimately claim that heritage.

So just what is the difference between Creoles and Cajuns?

For more than a century, the Creoles were the economic, social, and cultural leaders in New Orleans. Upper-class and urbane city dwellers, they spoke French, educated their children in France, clung to French traditions, and considered themselves far superior to any other residents of New Orleans. Those Creoles who remained in Louisiana were generally uneducated but felt cultured because they spent time at the French Opera House and hung out at cafes and the theater. They were especially contemptuous of crude, pushy Americaines who arrived in New Orleans after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Creole residents were glad that the Yankees and other "outsiders" lived primarily on the far side of Canal Street, in the Uptown area of New Orleans rather than in the French Quarter. But nothing the Creoles could do would stop the influx of newcomers. Within the next decade, at least 250 businesspeople were recorded as setting up commercial establishments in the city.

The majority were Americans who moved into Faubourg S. Marie, immediately dubbing the suburb a Yankeefied "St. Mary's." Their homes and businesses pushed out from New Orleans into what had once been Creole sugar plantations. The area today is the glass and steel muscle of the city's Central Business District (CBD), a true monument to early Northern expatriate entrepreneurs, such as builder and developer Samuel J. Peters. He was among many outsiders who burst on the New Orleans scene at that time to set the city's then languid business community on its ears.

The Creoles were hard pressed to keep up their traditional control over all aspects of New Orleans commence. They bitterly complained as English slowly became the language of enterprise in what had been their bailiwick for generations. On the other hand, the Americans muttered that street lighting and the few other civic improvements being made at the time seemed to be going into the Vieux Carre instead of the suburbs where they lived. Of course, travelers to New Orleans complained about the muddy streets in both parts of the town, not caring whether Creoles or Yanks were in charge of the purse strings.

In fact, there were two distinct New Orleans communities. The Creoles had their Place d'Armes (Jackson Square), while the Americans had Lafayette Square. The Creole social and business community focused around the St. Louis Hotel on St. Louis Street, while the Yankees congregated at the lavish St. Charles (which was surrounded by pigpens, according to New York journalist Abraham Oakley Hall, who wrote numerous columns about the Crescent City). The Creole Manison Row was along Esplanade near the United States Mint, while the Americans built their palatial homes along St. Charles. The Americans had the venerable St. Patrick's Church, and the Creoles worshipped in St. Louis Cathedral.

The expansive, tree-shaded, and flower-laden boulevards between the districts were called neutral grounds, a term still used today for the grassy dividers separating the traffic flow. There Creoles and Americans could warily - and relatively safely - conduct their business transactions, supposedly without getting into fights. The original neutral ground was what is now Canal Street.

The personification of the Creole was Bernard de Marigny, son of businessman Pierre Philippe de Marigny, who had made a commercial fortune under the Spaniards and was considered one of the riches people in America at the time. Young de Marigny's grandfather was Antoine Philippe de Marigny de Mandeville, stepson of the French royal engineer. Grandpa Marigny spent millions of francs building a villa north of Lake Pontchartrain where he could keep an eye on his vast land holdings. The mansion site is not the town of Mandeville (named after that distinguished, and rich, early colonist).

Little de Marigny might have gotten his easygoing contempt for money by watching his father in action. According to legend, the middle Marigny once hosted guests from France at an exceptionally fancy dinner, serving supper on special golden tableware that was then tossed into the Mississippi after the meal. The gesture meant that no one else was worthy of eating from the service.

De Marigny inherited seven million dollars when he turned fifteen in 1803. He spent much of it almost immediately on gambling and wild times and was subsequently forced to sell his beautiful estate, the Faubourg Marigny, to pay his debts. But de Marigny got in one last word, even as the papers were signed taking away his plantation. One of de Marigny's favorite games was Hazards, a dice game nicknamed le crapaud (the toad) by its players who squatted on their haunches like toads while playing. Because of his love for the game, he chose the name Craps for a lane in the new subdivision that had once been his property. Years later, the name was changed to Burgundy, following complaints by four churches on the street. They felt that such a gambling designation was inappropriate for their respective mailing addresses. When he was eighty-three, de Marigny died alone and almost destitute in a two-room apartment in his beloved French Quarter.

Another Creole noted for his opulent life-style was Charles Durand, whose beautiful Pine Alley plantation was on Bayou Teche near New Orleans. Preparing for the wedding of two of his daughters who were being married on the same day, Durand imported spiders from China to spin webs on three miles of trees leading to the mansion. Gold and silver dust was then sprinkled on the dewy webs early on the wedding morning much to the delight of the arriving guests. But such romantic opulence was not to last forever. The plantation was devastated during the Civil War and the buildings were destroyed. Today all that remains of the site just off Louisiana Highway 86 are the pine trees shading a long, narrow road leading to an empty field.

The Cajuns were more low key and fiscally conservative than the Creoles, finding sanctuary in parishes outside the city. Consequently, a contemporary visitor will had a hard time finding an "original" Cajun in New Orleans, much less an entire cajun neighborhood. However, an estimated one million people in Louisiana can trace their ancestry to the Acadian refugee families. People of the land, they still primarily make their living in the bayous as hunters, trappers, boatmen, fishermen, or off-shore oil rig workers. A hard-working people who love life, their philosophy remains laissez le bon temps rouler (let the good times roll). Yet for years being Cajun was considered lower class. Children were forced to speak English in schools and many of the family traditions began dying out as the bayous were developed, television intruded, and families dispersed in search of jobs.

Although few persons in New Orleans speak only French today, the Cajuns retain their unique speaking style and idiom. Their patois is similar to that spoken by residents of Quebec. Both dialects are akin to the language used by their ancestors, the first French Canadian settlers of 300 years ago. And in the past twenty years there has been a slow resurgence in appreciation for what is typically cajun.

New Orleans, however, has long been proud of both the creole and cajun influences that provided much of the underpinning of it cuisine, it emphasis on tradition, and its wonderful music.

Note: Remember that capitalized Creole and Cajun mean the people from those ethnic backgrounds, while lowercase creole and cajun are used as adjectives.