| |

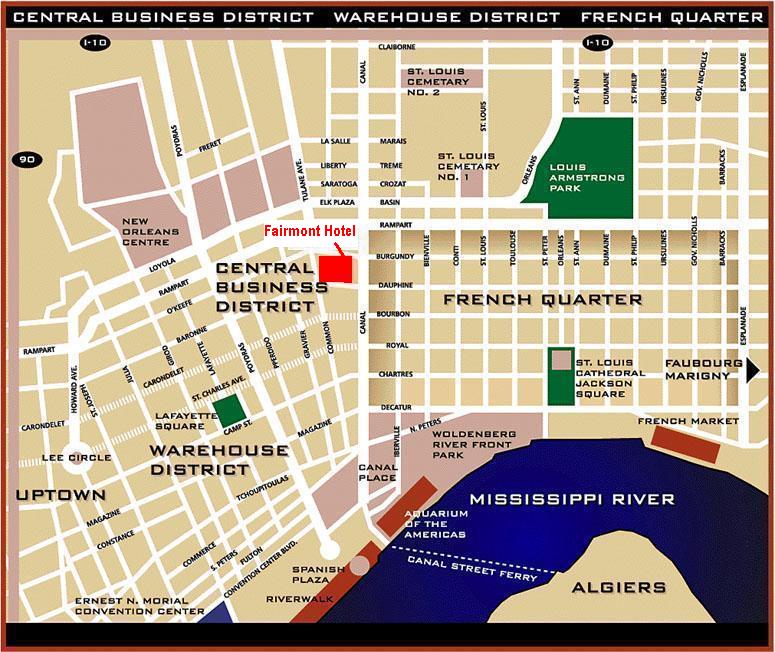

In Faubourgs Marigny

and Treme, mixed-race persons predominated. By 1840 femmes

de couleur libre owned about 40 percent of the property there.

Much of this was result of inter vivos donations from white

men who wanted security for these femmes de couleur, whom

the law did not permit to inherit real property. A double

creole cottage, for example, providedboth a home and a means

of support from the rented side.

French Quarters |

The golden age

in New Orleans for those Creoles fortunate enough to be free

was the 1830's and 1840's when they produced notable architects

and builders, artists and musicians, as well as manufacturers

and entrepreneurs in wide variety of businesses.

That golden

age is captured in the buildings they built and lived in. With

the advent of the Civil War three-fourths of the buildings lots

in Faubourg Marigny had been owned at least one time by

gens de couleur libres.

The

numbers in Faubourg Treme surpassed that. For example, Aristide

Mary, a free man of color, inherited from his Caucasian father

major buildings on Canal Street in the new American sector,

and leased both residential and commercial property to prominent

creoles and Americans prior to and following the Civil War.

He used the profits in 1892 to instigate the far-reaching lawsuit

Plessy v. Ferguson, led by Faubourg Treme French Speaking creoles

of color Homere Plessy and the writer Rudolphe Desdunes. Their

efforts to test the constitutionality of the Jim Crow law resulted

in the establishment of the separate but equal doctrine in public

areas. In these ways and others, New Orleans persons of color

profoundly affected American history.

These men and women are gone, but their

neighborhoods with buildings as solid as the social and legal

effects of their endeavors remain. House Histories disclose

that most persons of color who owned real estate owned slaves,

too. These slaves were tied to the properties of their owners,

rural and urban.

In fact, slaves, like some real estate, often

were included with the land title-not by law-but by tradition.

Examination of property titles shows how slaves were sold or

manumitted, how they bought their freedom or how they were exchanged

in tandem with house sales and property settlements.

Only

in New Orleans will building-watching, supplemented by archival

findings, reveal the full spectrum of

creole culture in the South. A census today shows that

Creoles hold ethnic majority in the city, but only architecture

and its accompanying records uncover the important role men

and women of African heritage played in developing this port

city.

Since 1726 talented architects and builders, ironworkers,

and real estate developers have emerged from this community

of personnes de .In Faubourgs Marigny and Treme, mixed-race

persons predominated. By 1840 femmes de couleur libre owned

about 40 percent of the property there. Much of this was the

result of inter vivos donations from white men who wanted security

for these femmes de couleur, whom the law did not permit to inherit real property.

A double creole cottage, for example, provided both a home and

a means of support from the rented side.

The French and Spanish creoles found Anglo-American attitudes

toward these women and other well-to-do personnes de couleur

libres atrocious. Americans even had the nerve to disapprove

of the long-established custom of placage. While the Code Noir

of 1724 and subsequent Spanish law, enforced by post-1803 American

regulations, prohibited marriage between whites and blacks,

slave or free, custom permitted white men to set up housekeeping,

a placage, with femmes de couleur libre, called their placees.

The children of

these arrangements were, acknowledged by their white father

before a notary, natural children, not illegitimate, and these

children inherited and equal share of their father's estate.

Such was the case in the

family of Narcisse Broutin, a notary and distinguished French

creole, descendant of the king's engineer who designed the Ursuline

Convent. In his will of 1819, Broutin declared that he had never

been married and had "no legitimate descendants."

He acknowledged his children Rosalie, Augustine, and Frumence,

born of Mathilde Gaillau, a free woman of color, who lived with

him in his dwelling in Faubourg Marigny. Broutin left these

children one-half of his property, all the common law allowed

for legitimate children.

Another important resident of the creole suburbs was Thomy Lafon,

homme de couleur libre and prominent businessman, philanthropist,

and benefactor to the community of personnes de couleur. He

retreated into the creole Faubourg Treme to avoid the new Americans.

His father was the French architect and surveyor Barthelemy

Lafon.

These are just a few examples of the hundreds of men and women,

black and white, who moved to the creole suburbs to preserve

their culture and to take advantage of Bernard de Marigny's

inexpensive lots on streets he gave esoteric names, such as

"Craps," the popular card game, or "Bons Enfants."

Lot prices started at about $108, suitable for the small investor.

French Quarter/ Faubourg

Marigny Gallery (other notables):

|

|