"Who built New Orleans, with its miraculous conflations of grandeur and decay

|

-- a city of indescribable beauty matched only by its equally distinct citizenry,

a people whose diverse and clandestine histories echo throughout the city's plastered walls? Whose hands gave rise to such eloquent and decaying monuments of cypress, plaster, iron and brick?" asks Mora J. Beauchamp-Byrd in "Raised to the Trade," a collection of art and essays surveying the cultural contributions of Creole craftsmen.

The answer, Beauchamp-Byrd writes, lies in the unique melting pot of people, skills and environmental constraints that guided the early development of the city.

Today, InsideOut begins a new occasional column profiling local artisans who have continued the tradition of individualized, hands-on work in a variety of building and decor trades. From blacksmiths to plasterers to potters, they have thrived here through the decades, and, as with our music and food and architecture, their craft helps make our city unique.

Invaluable knowledge

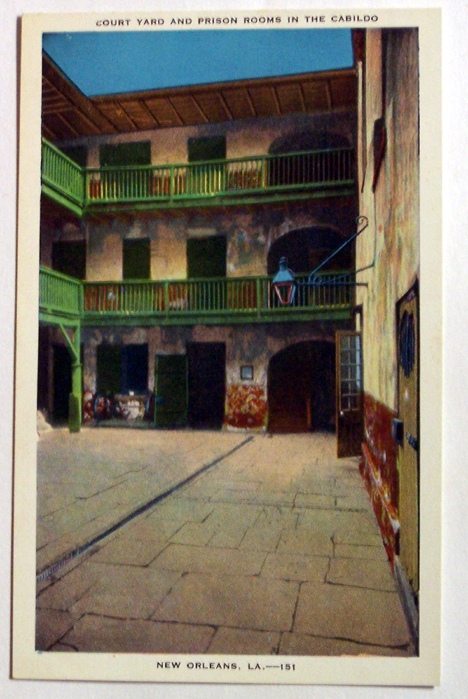

While it's easy to spot the European influences in the city's architecture -- the Spanish ironwork of a French Quarter balcony, or a Lower Garden District townhouse in the Italianate style -- the hands that built those houses can be traced largely to a Creole building tradition forged during the early 18th-century slave trade in Louisiana.

When West African slaves arrived in Louisiana, either directly from the continent or from the Caribbean, they brought with them a wide range of native skills and crafts. Some were building-related, such as carpentry and clay plastering. Others, such as basketry, fish netting and rope weaving, were not. Regardless of their relevance to home-building, the skilled crafts of this enslaved population began to blend with the trades of the Europeans.

"They brought lots of different skills. If you look at slave manifests, or slave sales documents, you can see the types of trades they were engaged in," said Sarah Elise Lewis, a scholar of New Orleans building arts.

West African and Caribbean builders also passed on their invaluable knowledge of home design suited to the tropics. Sketches of early Portuguese trading posts on the West African coast show their influence: The raised, multi-room, rectangular buildings with shaded galleries are obvious ancestors of the modern shotgun.

"Clearly, the Africans were in control of the architectural form of the buildings being constructed for the Europeans. They designed them, and they built them to suit their own social conveniences and architectural preconceptions. These buildings represented the earliest examples of Creole colonial architecture," essayist Jay D. Edwards writes in "Raised to the Trades."

European arrivals to New Orleans made their own contributions. From the Italians came marble-cutting; from the Germans, tinsmithing. Many early Creole houses, such as Madame John's Legacy in the French Quarter, show rafter designs blending the steep pitch of a Norman roof with the elongated, Caribbean-style roof necessary in New Orleans' tropical climate.