In

her book “Creole”, Sybil Klein states the

following: “Louisiana Creole cuisine” extends

to all those countries that trace the pattern

of the American slave trade route from West Africa to the Caribbean down to

thee north eastern coast of South s America and finally back up to Louisiana.

Once in the New World, these slaves not only grew the produce but were responsible

for preparing and cooking dishes that fed slave owners and slaves for hundreds

of years.

The result of what these millions of cooks created from the cultural

memory of cookingin Africa combined with the acculturated tastes and ingredients

from indigenous peoples in the Caribbean, South America, and Louisiana was

Creole cuisine.

The West

African connection to Creole cuisine is apparent upon examination of the culinary

habits of West African people. Jessica B. Harris traces the early diet of

West Africans from the Middle Ages.

She summarizes her findings: It all started

in Africa.Although some foods brought to the New World by slaves were indigenous

to Africa - such as okra, kidney beans,, black-eyed peas, and watermelon -

others were introduced to the African diet by European traders.

From the mid-sixteenth to the end of

the eighteenth century, the eating habits of Africa were transformed.

The

coconut tree arrived from South Asia sometime between 1520 and 1540, while

sweet potatoes and maize came from America in the same century.

The seventeenth

century saw the arrival of cassava and pineapple, while the eighteenth brought

guavas and peanuts.

The Portuguese are responsible for the transplanting to

Africa of those small hot chiles, as well as corn, cassava, and whites potatoes.

Other chile peppers and tomatoes were also transplanted from the New World.

African

link to Creole cuisine is perhaps strongest with regard to food preparation

techniques and cooking methods. The most frequent practice, however, was the

use of mortar and pestle for pounding dry peppers,, seeds, nuts, fruits and

vegetables

This technique of making a paste to add to sauces is probably

the origin of the Creole roux, the base for all gravies or sauces. When asked

for many recipes, Creole cooks automatically answer: “First you make

a roux.”

One of the meanings of the French roux is “brown sauce.”

According to Jules Faine, the Haitian Creole roux means “rouge,”

or red.

Creole

cooks not only brown the flour but they also brown the onion, garlic, and

other vegetable seasonings to add to gravies.

Browning some vegetables in

this manner releases their sugar content, thus caramelizing the vegetables

and giving them a sweeter taste.

Since many of the cooks during the period

of slavery were mulatto women, all of those definitions come together; following

the African tradition, Creole cooks served with many of their main dishes

delicious sauces made with the roux technique.

The Real Origins of Creole Crusine |

|

Another

example of an African cooking method is barbecue. “African

often roasted meats and served them with a sauce; . .

. throughout the New World, barbecues are

very popular only in those countries which

have or have had a sizable number of black

people.

” Creole fried chicken is another

dish that follows the African technique: “

the cook prepared the poultry by dipping

it in a batter and deep fat frying it…

[Also] throughout West Africa, it was

a favorite practice to serve chicken, grilled

or fried, with a sauce, over rice.”

Another

West African method of food preparation used by Creole

cooks is deep-fat frying of meats, fritters,

and a variety of fish and shellfish dishes.

This African

technique is one of the reasons for the

particular flavor of the Creole fried cuisine.

Africans cooked “by steaming, baking,

stewing, roasting, or frying. . . . Meats

were roasted, stewed, or fried. Although fish

was sometimes smoked ort pickled, it

was usually fried or stewed.

|

One

characteristic of Creole dishes common to Africa, the Caribbean,

South America, and Louisiana

is the hot spicy

peppers found in sauces and often added to dishes after

cooking.

Whether it is the extremely hot “pilly-pilly”

of West Africa, the burning hot “Bonda Mam’ Jacques”

(“Mme Jacques’ behind”) used in Martinique

and Guadeloupe, the very hot chili jalapeño and habanero

peppers of the Caribbean and South America ,

or the hot, hot cyenne pepper of Louisiana, this tongue tingling

spiciness is the signature of Creole food.

|

Some Louisiana seafood gumbos are flavored

with a Choctaw Indian spice called file, which also functions as a thickening

agent. “In much of West Africa ‘gombo’ means okra.”

Okra

is used in gumbos for thickening the sauce. Creole cooks prepare a variety

of bean dishes. As in West Africa, the beans are boiled and a spicy sauce

is made from or combined with the beans.

Louisiana’s own Creole red beans

and rice is cooked that way with the addition of a salt meat or sausage for

seasoning. Add coconut milk and the dish is known as Arroz con Frijoles in

the Dominican Republic. Congris, a specialty of Cuba, is also a version of

red beans and rice. In Haiti they are called “Pois Rouge en Sauce”

or “Pois et Riz Colles.”

Jambalaya and Mirliton are other Louisiana

Creole dishes with Afro-Caribbean links.

Jambalaya is said by one author to

be an African dish, based on her identification of the word as a combination

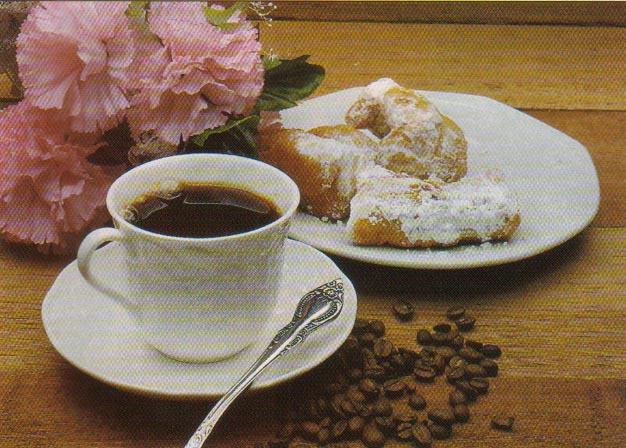

of jamba (ham) and paella (rice), the main ingredients.Another fritter or

fried doughnut is the beignet.

Beignets are deep-fried African style, sprinkled

with powdered sugar, and served hot with café au lait.

The praline, a Creole candy made from

sugar, cream, and pecans, was supposedly invented by the cook of one Marshall

Dupleeses-Preslin (1598-1675) and remains a popular sweet in New Orleans.

It can also be found in other parts of the southern United States.

Creole

cookery has an amazing legacy from four continents. It is no wonder that Creole

is so popular around the world.

The excellent use of indigenous spices and

African cooking methods combined with talent for developing the new from the

old make Creole food a valuable resource with deep roots in the African diaspora

and an important element in defining Creole culture.”